bureaucracy

understanding how actions taken with the best of intentions can put your organization in a straightjacket

Successful organizations maximize the formula shown below:

Meaningful output: meaningful output is any output aligned with the organization’s purpose. For example, Feed My Starving Children’s purpose is to deliver food to impoverished areas. A meaningful output for them is a successful food delivery.

Resources spent: this is mainly just time and money.

As an organization, you have two levers to improve: increase meaningful output while using the same amount of resources, or maintain the same meaningful output while decreasing the amount of resources spent. When companies hire people, they’re hoping that their meaningful output will increase far more than the increase in cost, and when companies conduct layoffs, they’re hoping that their meaningful output will reduce much less than their resources.

Few things frustrate me more than bureaucratic organizations. They completely butcher the formula above. Within the mess of systems, committees, and processes, the production of meaningful output becomes impossible, and sustaining this complexity requires an immense amount of resources.

The worst part is that they’re extremely static and difficult to change. This is because:

Inertia - the size and complexity of bureaucracy create tremendous inertia behind the status quo. It takes an overwhelming amount of energy to both map it and change it in a positive way. Few people are willing to take the plunge, and fewer power brokers within the bureaucracy will support any change because it would threaten their position.

Illusory work - the effort required to survive within the bureaucracy leaves little room and energy to change it. Here’s an example from Google:

Google has 175,000+ capable and well-compensated employees who get very little done quarter over quarter, year over year. Like mice, they are trapped in a maze of approvals, launch processes, legal reviews, performance reviews, exec reviews, documents, meetings, bug reports, triage, OKRs, H1 plans followed by H2 plans, all-hands summits, and inevitable reorgs. The mice are regularly fed their “cheese” (promotions, bonuses, fancy food, fancier perks) and despite many wanting to experience personal satisfaction and impact from their work, the system trains them to quell these inappropriate desires and learn what it actually means to be “Googley” — just don’t rock the boat. — source

Organizations don’t just naturally become bureaucratic as they grow; they become bureaucratic as a result of deliberate decisions made by leaders who at the time believed they were doing the right thing.

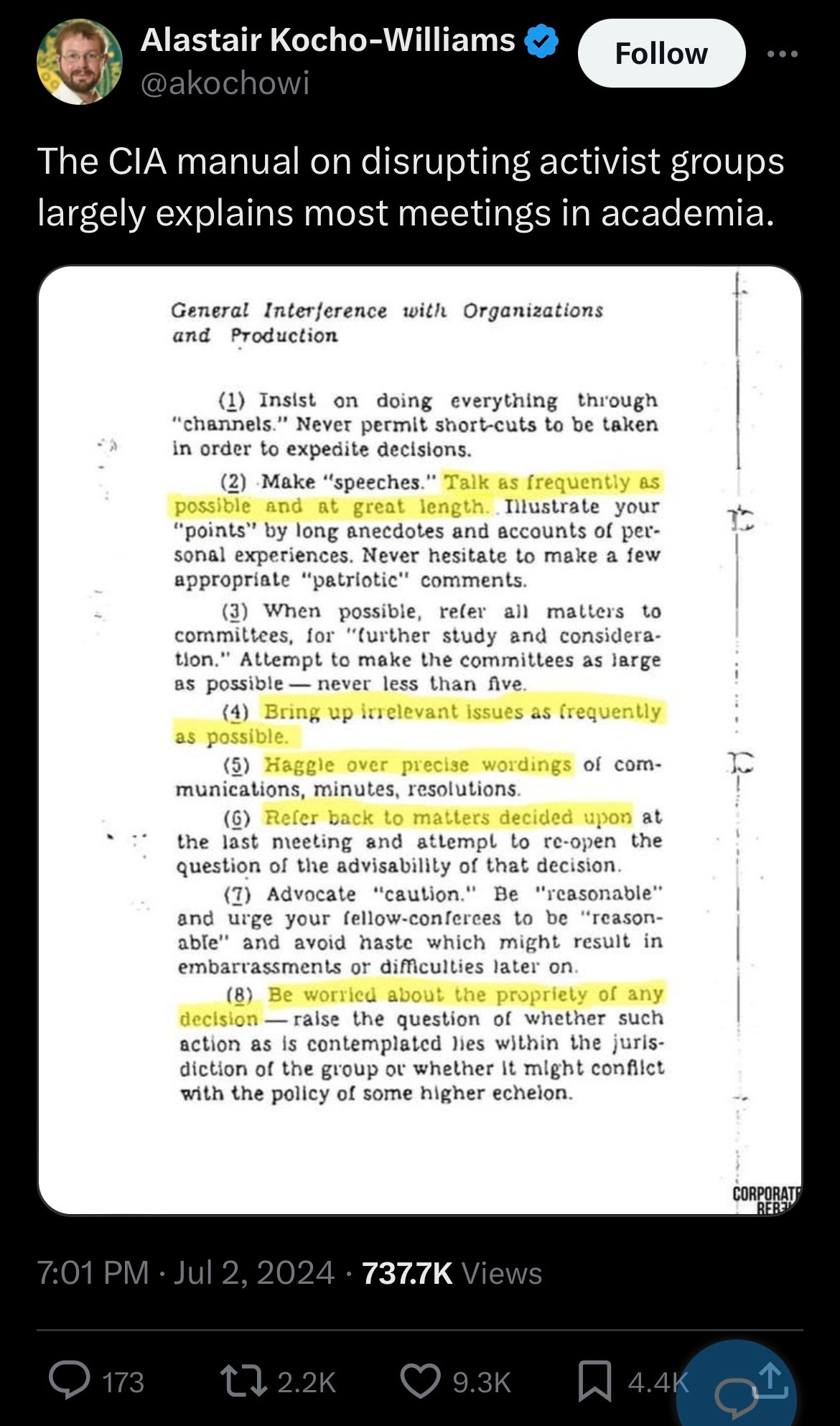

The CIA provides evidence that bureaucracy can be built through distinct actions. Here are a few guidelines from their handbook on how to disrupt activist organizations:

In the abstract, a lot of these actions seem benign!

“Haggle over precise wordings” - it’s hard to object to people showing attention to detail because it seems as if they’re extremely invested in the outcome.

“Refer all matters to committees” - how can you object to delegating decisions to subject matter experts?

“Be worried about the propriety of any decision” - it seems extremely important to ensure that you’re acting within scope and not exposing your organization to risk.

Yet the CIA used these tactics effectively to prevent groups from achieving their aims.

I think that leadership mistakes that cause bureaucracy to develop come in two flavors:

Poorly designed incentive systems - many incentive systems punish mistakes but fail to reward successes, causing organizations to be overly risk-averse. For example, the FDA is punished for permitting harmful drugs to be sold on the market, but they’re not punished for stalling research that could save lives and they’re not rewarded for supporting transformative innovation.

Loose coupling of systems with desired outcomes - there’s often minimal connection between systems and processes put in place and desired organizational outcomes, even if the systems seem benign or helpful. For example, in engineering teams, it may seem like a good and safe idea to get consensus from leadership on every important architectural decision, but the desire for consensus can conflict with the organizational goal of releasing features at a high velocity to remain competitive.

poorly designed incentive systems

*I’m paraphrasing the work of Scott Alexander and Jason Crawford here

Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) are panels that review the ethics of medical studies. They’re a relatively recent thing. Before the advent of IRBs, doctors were encouraged to independently study topics of interest without any guidelines for how these studies were to take place. Many ethically ambiguous studies took place. For example, during World War II, researcher James Shannon made tremendous strides in malaria research (which he eventually won a Presidential Order of Merit for), but his research involved injecting mentally ill patients with malaria.

Eventually, in 1974, after egregious studies like the Tuskeegee Syhpillys Experiment, IRBs were instituted to ensure studies followed certain ethical standards, like getting informed consent from patients. This worked well until 1998 when a patient died during an asthma study at Johns Hopkins, after which all studies at Johns Hopkins and several other research studies were shut down. Thousands of studies were ruined, and millions of dollars were wasted.

Nowadays, IRB oversight has become a straightjacket. Scott details his experience:

When I worked in a psych ward, we used to use a short questionnaire to screen for bipolar disorder. I suspected the questionnaire didn’t work, and wanted to record how often the questionnaire’s opinion matched that of expert doctors. This didn’t require doing anything different - it just required keeping records of what we were already doing. “Of people who the questionnaire said had bipolar, 25%/50%/whatever later got full bipolar diagnoses” - that kind of thing. But because we were recording data, it qualified as a study; because it qualified as a study, we needed to go through the IRB. After about fifty hours of training, paperwork, and back and forth arguments - including one where the IRB demanded patients sign consent forms in pen (not pencil) but the psychiatric ward would only allow patients to have pencils (not pens) - what had originally been intended as a quick note-taking exercise had expanded into an additional part-time job for a team of ~4 doctors. We made a tiny bit of progress over a few months before the IRB decided to re-evaluate all projects including ours and told us to change twenty-seven things, including re-litigating the pen vs. pencil issue (they also told us that our project was unusually good; most got >27 demands). Our team of four doctors considered the hundreds of hours it would take to document compliance and agreed to give up. As far as I know that hospital is still using the same bipolar questionnaire. They still don’t know if it works.

He summarizes his thoughts on the bureaucratic regulation here:

So the cost-benefit calculation looks like - save a tiny handful of people per year, while killing 10,000 to 100,000 more, for a price tag of $1.6 billion. If this were a medication, I would not prescribe it.

Initially created to protect patients from being taken advantage of and support doctors in study design, the IRB has now become a monolith, strangling researchers and imposing a significant cost on the medical industry.

How did we get here?

Jason describes the process like this:

The IRB story illustrates a common pattern:

A very bad thing is happening.

A review and approval process is created to prevent these bad things. This is OK at first, and fewer bad things happen.

Then, another very bad thing happens, despite the approval process.

Everyone decides that the review was not strict enough. They make the review process stricter.

Repeat this enough times (maybe only once, in the case of IRBs!) and you get regulatory overreach.

It’s a case of poorly designed incentives. The IRB receives no reward for enabling or supporting research, and it receives no recognition when the research directly saves or improves many lives. Instead, it is given all the blame for any harm that comes to patients. This is especially damaging during a time when everyone is lawyering up; mistakes are extremely dangerous for the IRB and the medical industry. This means they have an incentive to prevent any mistake from happening even if it comes at the cost of good research.

While the IRB is an extreme case, I think every organization has seen the installation of processes and systems after a mistake to eliminate mistakes from happening. It’s basically standard corporate vernacular to say “This wouldn’t have happened if a better system was in place.” Everyone wants a new system or process.

Tying this back to the formula at the beginning, typically the new systems and processes will consume significant additional resources while only marginally improving the meaningful output produced by the organization. In the case of the IRB, it’s adding billions of dollars and innumerable hours in cost while harming research velocity with the outcome of saving a small number of lives. I agree with Scott - this is a poorly optimized equation.

Instead, I think a better approach is to have a different mentality around mistakes. I really like the concept of statistical process control (SPC). The goal of SPC is to improve quality by reducing variance. It understands certain outcomes as simple variance, and the goal of the few processes in place is to reduce variance while improving key organizational metrics.

I think the focus on metrics and outcomes helps fight back against the tendency to add reviews and approval processes everywhere, only adding them in situations where they directly and meaningfully improve outputs (i.e. we’re doing this because it helps us achieve our purpose, instead of we’re doing this because we’re afraid of making mistakes). I know it’s a subtle distinction, but I think it’s a meaningful one. It requires teams to be really, really intentional about what their goals are and ruthlessly stick to them. It takes effort, but I think it’s worth it.

loose coupling of systems with desired outcomes

Everyone has been in meetings where the purpose is unclear, the meeting leader waxes poetically, and you leave feeling dumber and less motivated than you did at the start. This is especially true of recurring meetings; very rarely are they an effective use of time. This is an example of a system that’s not aligned with a desired outcome. If you run a meeting in which there’s no clear value returned from it, you’ve invested organizational resources while not increasing meaningful output. This is the opposite of what you should be doing. Cardinal sin!

Here are a couple more examples:

Systems to build consensus - it takes a lot of effort to get people aligned. Even though this is something that seems positive, it is very rarely worth the effort. Consensus can be affected by group decision-making biases leading to worse decisions, and it can prevent organizations from making bold decisions that can have outsized benefits. Additionally, consensus is fragile; people’s minds change faster than you might imagine.

Status updates - standup meetings are a meme these days. Again, a system born out of good intentions (we should all be on the same page and work collaboratively!), but often devolves into micromanagement and frustration, never really delivering value for the people in the meetings. Another system that is rarely aligned with desired outcomes.

Sometimes, the answer to fixing a poorly designed system is to just tweak the existing system. In the example of meetings, perhaps the meeting is necessary to get everyone on the same page, but the lack of a prepared agenda and post-meeting recap is preventing that meeting from being useful. Those are easy changes that flip the equation and get the activity back on track to being something meaningful.

Other times, the answer is to simply remove it with the understanding that either the problem that the system was meant to solve no longer exists, or that the problem exists but the system is doing nothing to improve it.

I think there are 4 components to effectively designed systems:

Clear problem statement - each system or process must be coupled with a clear problem that it is meant to solve. For example, a problem statement could be “Our product team and marketing team are unaware of what they’re each working on, causing our marketing team to have to frequently rework their assets and communications.”

Clear target metric to improve - using the same example above, a target metric could be the number of times the marketing team has to redo their work.

Intentional system design - an example here could be “To make the two teams aligned, we’re going to add a monthly meeting for each team to share their roadmap. The goal of this meeting is to reduce the work done by the marketing team”

Commitment to study the metric - this is crucial! Many people just forget about why systems are installed or what they’re meant to fix. You have to intentionally study the metric and make observations to see if the system is actually doing what it’s meant to. This will let you know if it’s worth keeping or not. An example could be to commit to revisit the metric in 3 months and assess if there has been a measurable improvement.

The key here is that these systems have to be malleable. Just because it worked for a short period doesn’t mean it will work forever! Perhaps the problem no longer exists, or perhaps the organizational goals have changed. Any change in the surrounding context requires you to reassess the dependent systems and tweak them accordingly. If you don’t do this, you’ll end up stuck in an organization where people do things all the time for unintelligible reasons in ways that are not tied at all to meaningful output. This isn’t a rare occurrence at all.

None of this is easy. To do this right, you have to deeply understand your organization and its purpose. You have to be deliberate with your actions and intentions, frequently revisiting things and tweaking them as the surrounding context changes. You have to be constantly aware of the state of your organization and the habits and systems that are being built.

To make it harder, it is not sufficient to do something that is a “best practice”. You must marry the right action with the right context because if it’s not coupled well, you’re on the way to creating a bureaucratic maze.

Reasons for doing things matter. Purpose and intentions matter. The problems you’re solving for matter. You must be critically aware of all of these factors while building an organization, or else you’ll be flying blind into a storm of your own creation.

Further reading: